From teaching children to draw straight lines in numeracy

classes to insisting on specific fingers in music lessons, we all have

championed principles around which our profession has been built with neither

any consideration for the uniqueness of learners nor any thought for their

individual preferences. What if I want to draw curves? What if the idea of not

pleasing my teacher terrifies me? What if I prefer to have my right hand up on

the saxophone? Why doesn’t anyone tell instrument makers to make saxophones the

other way? If everyone thought the same way about the same things there would

be no inventors on the planet.

We evolved ‘standard’ expectations which have held too many

children back for too long. We think this or that is why they are in school. We

leave little room, or none at all, for expecting them to be themselves. Sport

coaches have had to bench students who got low grades in math. Worse, we sold

these ideas to parents. At a time the best singer in school got denied

performances because her dad felt awful with her grades in an examination which

has no bearing on the girl’s preference – music. Good to mention that some

parents didn’t buy into it. I once had a mother who pulled her daughter out of

the laboratory to my music room afternoon after afternoon.

Understand, students are humans, albeit young. They came to

this planet on purpose. That one reason should drive our school system. The day

– or semester – we begin to care less about language grades when a student is

soaring in physics, is the day school gets worth their while. Let them be! Let

them take the lessons knowing they don’t have to fit our stereotypes. We have

gained too little developing children from neck up. This principle of erroneous

perception of learners’ purpose is a societal fault line needing an

immediate fix.

Fixing the Pompous Principle

At a jazz masterclass I asked a Berklee professor what was

paramount on his mind whenever he taught his students. Permit me to paraphrase

his answer here: “I know they have come to learn, but I also know I could learn

from them.” A professor of music, I had thought, shouldn’t have anything to

learn in that field from anybody for that matter, let alone a student of music.

Well, I was wrong. He learns a great deal from them. In contrary, I hear about

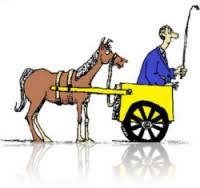

a teacher shutting up a child who finished a sentence for her. Why teachers feel

like horses drawing chariots will never be clear to twenty-first century learners.

The time has come for a test drive with students in the

driver’s seat. We shouldn’t be afraid to arrive at a place where our lesson

plan is no longer necessary especially if it can’t be adjusted in the learner’s

favour. Moreover, we should stop marking them wrong. Simply schedule a

discourse over what the lesson was about allowing them to share how they

conceived it. Then would we realize how wrongly we have been teaching and grasp

how best to communicate in such ways as they might be able to learn. The way

doctors think they are greater than their patients (until they get down with

something) is the same way teachers think they know more and can do better than

their students, until they find the words of Will Rogers to be true: “Everybody

is ignorant, only on different subjects.” Whether or not it evolved from the

school administrator’s perception of herself as higher than the janitor, we need

to correct this professional fault line of superfluous status now and always.

Fixing the Process Principle

If you don’t like meetings don’t become head of anything. In

the world we now live in there are many of them lacking objectivity. Then you

have to do a round of the stores, window-shopping. You would follow that up

with drawing papers to back-up your proforma invoice. What you have to do next

is another meeting with your supervisor to defend the papers you filed. There’s

one more meeting after that. It’s holds with the school administrator and, if

you don’t sound convincing enough – even if your students badly need the item

you requested – you’d need yet another meeting with the purchasing manager.

Beyond this point you have to hope the accounts director doesn’t think it’s too

expensive. And on it goes until you start wondering if you were hired to teach

or meet.

Creativity is lost in the maze of too many steps. Once the

path is cluttered the person is confused. The surest way to sicken a system is

to hire straight-jacket bureaucrats in the name of processes. An indication of

this may be found in meetings and procedures devoid of empirical substance. When

there is only one way to do right there is one certain result – death, from boredom and/or

disorientation. Nothing matches flexibility when it comes to running a

community of learners for passion is certain to wane should you have to sign

papers in four offices to get anything done. They were supposed to help keep a

structure in place but they do little else than ensure it crumbles on its own

head; or worse, crack open to swallow everything serving it. And so must we

overcome this administrative fault line or run the risk of demotivating our

work force.

Fixing the Promoter Principle

Discussing the fault lines in our education systems would be

an incomplete attempt if we don’t zero-in on the classroom experience. Students

sit in class for endless minutes listening to an ‘expert’ rant about the

wildest topic from the strangest subject. It was one head of school who made me

realize how strange the treble clef seems to dyslexics. I had always thought it

a very beautiful curve around five lines and the spaces in between so long as

you ensure it runs around the second line. Now, what in the world have I just

described and why should it run clock-wise around the second?

Seeing that all students can’t learn this way, I chose ever

since to trivialize and simplify that pitch symbol. To make it seem less of a

big deal, I suggest its function and make them play with it; to make it easier

to draw, I show rather than tell while engaging them with the actual pencil

work. This is what the science teacher ought to do rather than talk and give

lengthy notes to eleven-year-olds on separation techniques. Mix grains of sand

with a pinch or two of salt (sodium chloride) and share how this mixture could

be separated. Then leave them to do it. We would need fewer preps if we spread

out contact periods for real-time learning experiences than hoping they can ram

it in their heads from notes and textbooks. This productivity fault line can

be mended.

Fixing the Pointless Principle

There are more written assessment instruments in the world’s

educational institutions than there are skill-based assessment structures. What

is the appropriate measure of competence in vocational subjects – performance

and creativity or explanation in writing? Americans began to worry when jobs

went to Chinese firms no less than Africans express frustration when projects

go to German companies. How did we evolve a society in which government

contracts are won by foreign construction firms unchallenged by its people who

are not any less trained or skilled?

Government is constantly under pressure to create more jobs

at a time when schools are attempting to incorporate more vocational subjects

into the curriculum. Which should we clamour for – jobs in corporations or

entrepreneurial vocations – if we were certain that either would function at

their very best? One reads in the dailies sickening reports of ailing African

leaders who spend billions of dollars on foreign medical treatments, the kind

of funds more than sufficient to fix their country’s health systems. Why should

we raise professors of medicine who can’t/don’t treat their country’s ailing

government officials because foreign medical trips are alluring tours?

Although fixing fault lines in governance, key to a

better communal experience, is the responsibility of public office holders, it

must begin in school. No government will operate better than its nation’s

education system. No people will emerge a leader better than its finest

constituent fabric.